Outcomes

Does CV inflammation increase the risk of mortality?

The evidence is mounting: Inflammation is not only associated with increased CV risk and worse CV outcomes, it’s also a key suspect in CV death.1,2

Connecting the clues

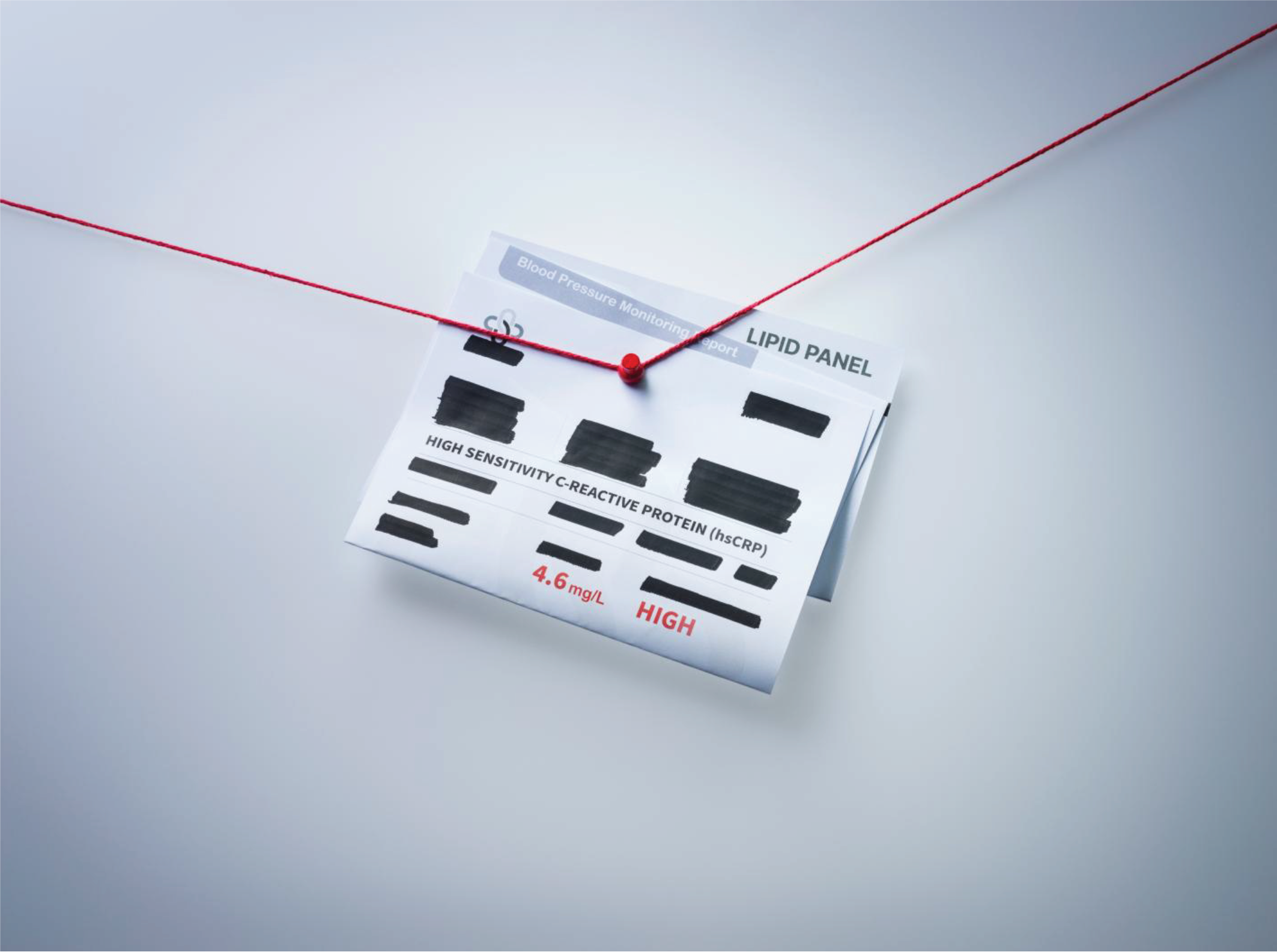

Elevated levels of inflammation in CVD are associated with increased risk of CV death in patients with ASCVD and prior MI:

† Adjusted for age, sex, time since myocardial infarction, hemoglobin, eGFR, undertaken procedures, comorbidities and ongoing medications. Compared with hsCRP < 2 mg/L, patients with hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/L had a 1.44 (95% CI [1.29, 1.60]) higher risk of CV death.2

Inflammation leaves its fingerprints across many serious CV events

In patients with ASCVD

Inflammation can increase the risk of MACE, hospitalization for heart failure, and all-cause mortality:

In patients with prior MI

Inflammation can increase the risk of MACE and all-cause mortality:

† The adjusted relative rate of events in participants with hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/L (vs. hsCRP < 2 mg/L) was 24% higher for heart failure (HR 1.24; 95% CI [1.20, 1.30]). Adjusted for age, sex, time since ASCVD, eGFR, albuminuria, comorbidities, undertaken procedures, and ongoing medications.4

‡ The adjusted relative rate of events in participants with hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/L (vs. hsCRP < 2 mg/L) was 35% higher for all-cause mortality (HR 1.35; 95% CI [1.31, 1.39]). Adjusted for age, sex, time since ASCVD, eGFR, albuminuria, comorbidities, undertaken procedures, and ongoing medications.4

¶ Adjusted for age, sex, time since myocardial infarction, hemoglobin, eGFR, comorbidities, undertaken procedures, and ongoing medications. Compared with hsCRP < 2 mg/L, patients with hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/L had a 1.28 (95% CI [1.18, 1.38]) higher risk of MACEs.2

§ Adjusted for age, sex, time since myocardial infarction, hemoglobin, eGFR, comorbidities, undertaken procedures, and ongoing medications. Compared with hsCRP < 2 mg/L, patients with hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/L had a 1.42 (95% CI [1.31, 1.53]) higher risk of MACEs.2

The real-world evidence is clear

A real-world Swedish study of 17,464 MI patients uncovered more evidence supporting the case against inflammation. As well as demonstrating the prognostic significance of hsCRP levels, the study found that most patients with MI exhibited elevated hsCRP levels.2

hsCRP Level and the Risk of Death or Recurrent Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Myocardial Infarction: a Healthcare‐Based Study

publication